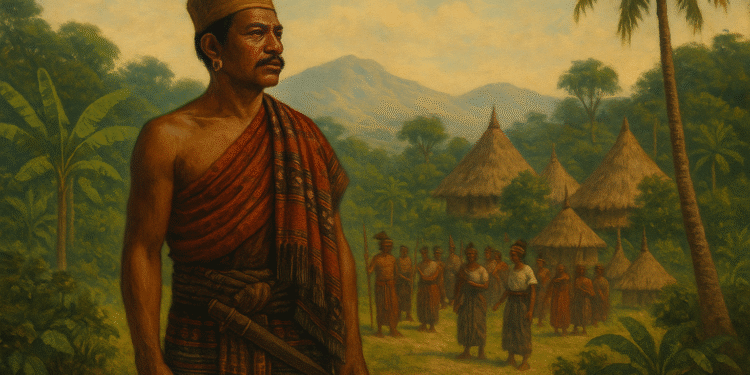

The title Liurai holds deep cultural and historical significance in the island of Timor, representing a unique blend of indigenous governance, spiritual symbolism, and colonial adaptation. Rooted in the Tetun language, Liurai translates to “surpassing the earth”—a name that reflects both reverence and authority in traditional Timorese society.

Origins and Symbolic Power

The term Liurai was originally linked with the ancient kingdom of Wehali, located on the southern coast of central Timor—now part of modern-day Indonesia. In this sacred political structure, Wehali’s highest spiritual figure was the Maromak Oan (literally “Son of God”), a ritually passive figurehead. While the Maromak Oan embodied spiritual continuity, it was the Liurai who served as the executive authority, managing the temporal affairs of the land.

This model of spiritual-political dualism extended to other prominent Timorese polities, including Sonbai in West Timor and Likusaen (Liquica) in East Timor. Each of these regions had their own Liurai, creating a symbolic tripartition of Timor’s traditional power structure. These rulers were not just local chiefs—they were the recognized intermediaries between sacred power and the practical necessities of governance.

Evolution Under Colonial Rule

Over time, especially during the 19th and 20th centuries, the title Liurai became increasingly widespread. In the Portuguese-administered East Timor, the term came to refer to virtually any native ruler, regardless of the size or importance of their domain. In contrast, in Dutch West Timor, the title retained more exclusivity and was generally reserved for rulers of higher prestige, such as those of Sonbai and Wehali.

In Dutch records and political organization, rulers were often called by the Malay term raja. However, different communities also maintained their own indigenous terms—usif (meaning “lord”) was used among Dawan-speaking groups, while Tetun speakers also used the term loro (meaning “sun”) to refer to their leaders. This diversity of titles reflected the cultural richness and linguistic variation across the island.

Colonial Transition and the Decline of Authority

The traditional power of the liurais began to wane following the Boaventura Rebellion of 1912, a major uprising against Portuguese colonial rule. The Portuguese response was swift and forceful, leading to a shift in how local rulers were chosen. After the rebellion, the colonial authorities began appointing liurais based more on their loyalty to Dili than on traditional legitimacy. Political loyalty and alignment with colonial interests became key criteria, often overriding ancestral or customary claims to leadership.

As a result, many traditional power structures were gradually eroded. The liurais, once autonomous leaders and spiritual stewards of their people, became increasingly integrated into the colonial system as administrative figures rather than traditional monarchs.

The Liurai in Modern Timor

Today, the liurai no longer hold official governmental authority in Timor-Leste (East Timor) or the Indonesian part of Timor. However, many of their descendants continue to be respected figures within their communities. These families often play important roles in local ceremonies, cultural preservation, and even national politics. In fact, some scions of liurai families have gone on to hold significant political positions in post-independence Timor-Leste, drawing on their ancestral legacy and enduring local influence.

Despite the loss of formal power, the liurai title continues to carry cultural weight. It remains a symbol of a deep-rooted heritage—one that predates colonial borders and continues to inform the social fabric of Timorese identity.

Enduring Legacy and Cultural Significance

The history of the liurai is a testament to Timor’s complex past—a fusion of sacred authority, indigenous governance, and colonial disruption. While no longer enshrined in law or constitution, the legacy of the liurai lives on through oral histories, family lineages, and cultural memory. As Timor-Leste continues to define its post-colonial identity, the role of these traditional leaders—both past and present—offers valuable insights into the resilience and continuity of Timorese society.